Events – both real and imagined – set off strong emotional reactions in us. And sometimes the situation in which this happens means that it would be better to respond with less emotion. For instance, we might be quite happy with crying at what happens in a movie when in our own home, but prefer to stay dry-eyed when in the cinema (not that there is anything wrong with crying in public!). Alternatively, we might be really excited at news that we have just been promoted and want to jump up and down with delight, but we might choose not to do this in front of someone who has just had their application for promotion rejected.

How do we regulate our emotions in these circumstances? What systems in the brain are available to help us with this task?

Research suggests that there are at least three ways that we generate emotions (Gross, 1998; Kool, 2009):

- Attention: We select particular parts of our sensory input on which to attend. The emotions generated by a particular event will therefore depend in part on which aspects of the event are captured by our attention.

- Cognition: We evaluate events in relation to, for instance, our goals, expectations and our ability to control outcomes. In addition, current events will activate memory for past emotional events thus our interpretation of past experiences will influence our experience of current events. Thus, individuals can have different emotional responses to the same event depending on the way that they appraised similar events in the past and this event in the present.

- Body: We evaluate events with respect to the physiological changes that these create in us including facial expression, body position and movement, and internal visceral responses (for example, butterflies in the tummy, shallow breathing, hairs rising on the nape of our neck).

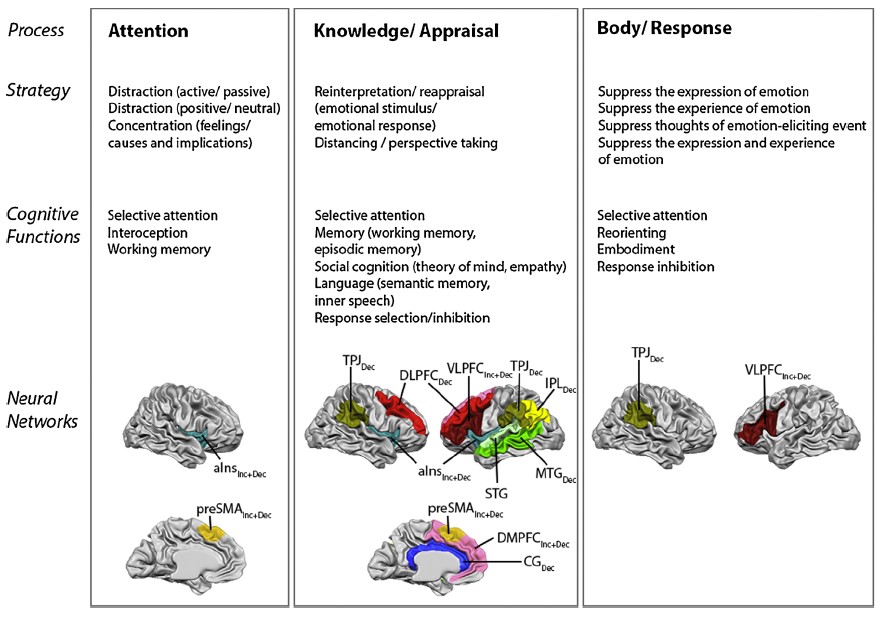

Since there is more than one system for generating emotion, it is likely that there are several systems for regulating emotion. Again, research has demonstrated that there are at least three regulation systems, each based on the reacting to a particular way in which emotion is generated:

- Need-oriented emotional regulation: This targets the attention system by, for instance, reducing a negative emotional response in a situation in which you need to be more resourceful by thinking positive thoughts (distraction) or by involving yourself in a different task that requires you to pay close attention (concentration). This changes the focus of attention in order to regulate the emotional response. This method of emotional regulation uses distraction techniques.

- Goal-oriented emotional regulation: This targets the cognitive system by, for instance, considering whether the event will feel the same when reflecting on it from a place in the future or considering whether anything good might come from an event that currently is perceived to be negative. Changing perspective can change our appraisal of the goal of events thus moderating our emotional reaction to them. All of the methods of cognitive reappraisal fall under this category.

- Person-oriented emotional regulation: This targets our visceral response to events by changing our physiology. An example of this type of regulation would be counting to ten, or breathing deeply when faced with an intense emotional response. This includes techniques that suppress the emotional reaction.

A meta-analysis by Morawetz, Bode, Dentl and Heekeren (2017) systematically reviewed papers that had used brain imaging to determine the neural networks responsible for different forms of emotional regulation. This showed that there are distinct neural networks underlying the different types of emotional regulation (Taken from Figure 4: Morawetz et al, 2017).

On viewing these strategies and realising the complexity of the systems in the brain that we have available, it became apparent that there might be room to learn to use different strategies, or even different combinations of strategies, for different situations. For instance, re-interpreting the event and then doing something which requires concentration while the subconscious mind processes the event might be a great combination in some circumstances. Or, when it is difficult to concentrate and therefore doing something which requires concentration is unlikely to work, it might be better to change the physiological response by changing your breathing pattern, putting on some lively music, and dancing. Reflecting on the opportunity that the emotional event gave you to enjoy your favourite music might then be added as a way to reappraise the event.

Reflection:

- Consider the emotional regulation strategies that you use regularly:

- Which types of strategy are familiar to you?

- Which types of strategy might also be of use to you and in what combinations?

- What steps might you take to add some new strategies to your repertoire and where might these be most useful to you?

Author: Professor Patricia Riddell

Thanks Patricia – this is a really helpful summary of emotional regulation.

I’m really looking forward to the next weekend of training.

Thanks Karen – I found this useful and so hoped the group would too

See you in April

Trish